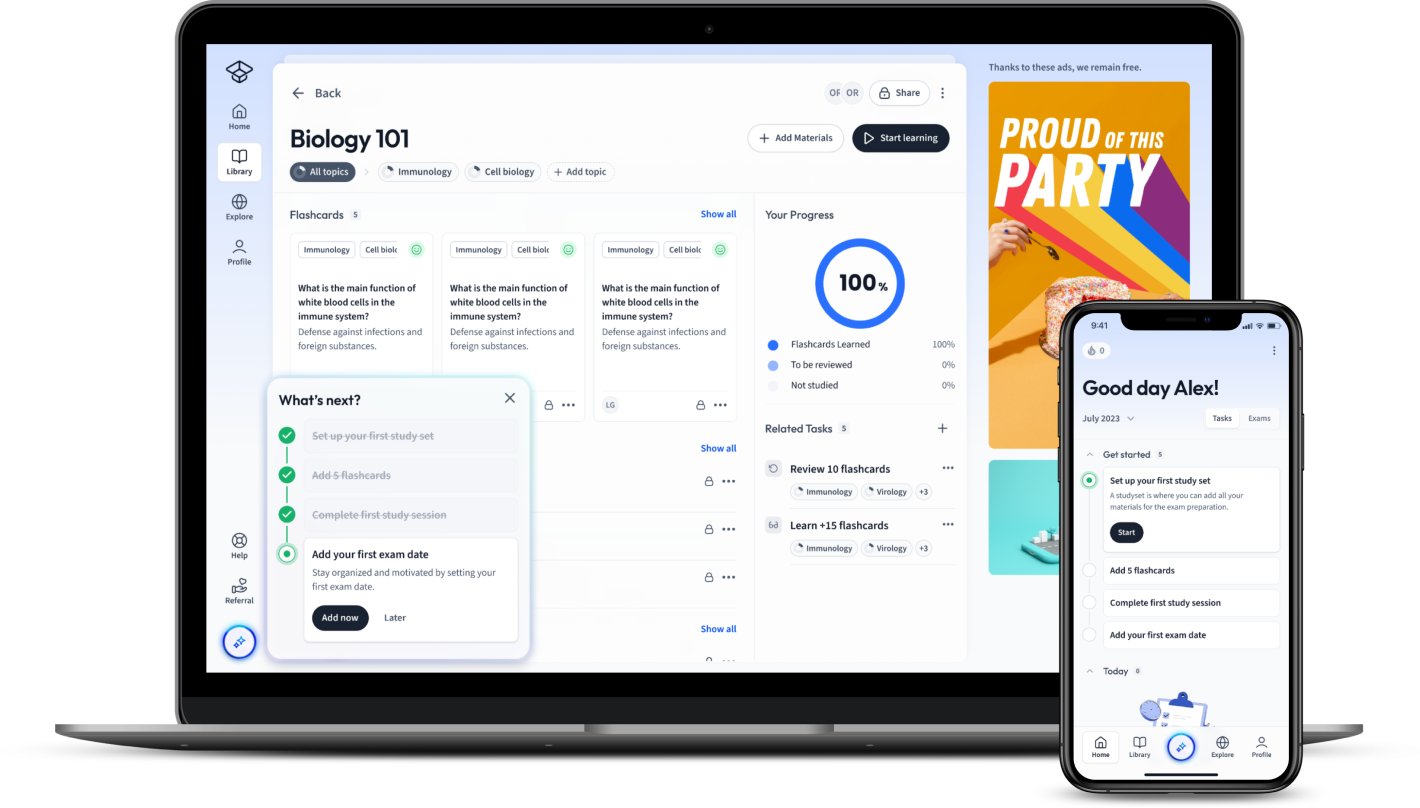

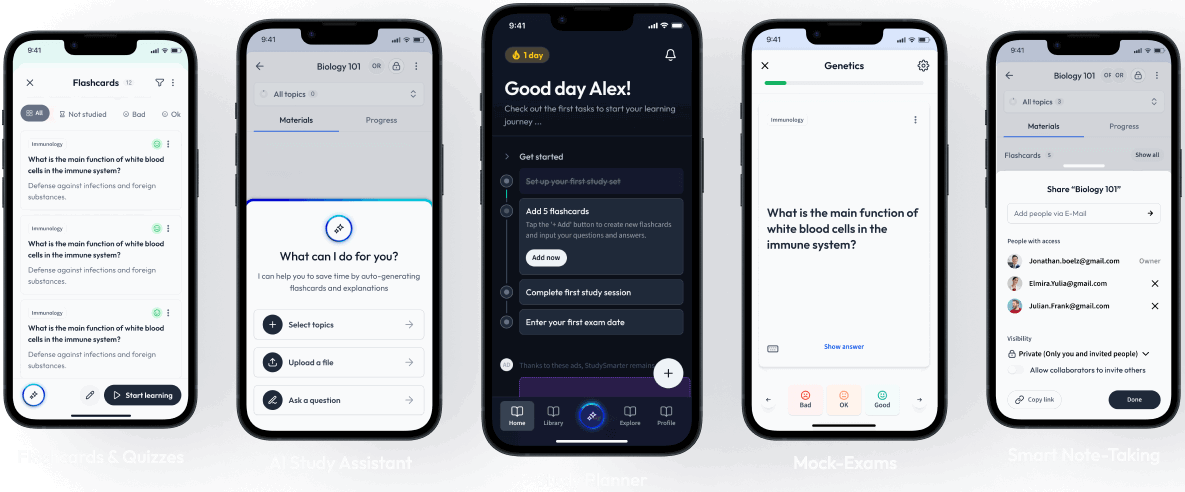

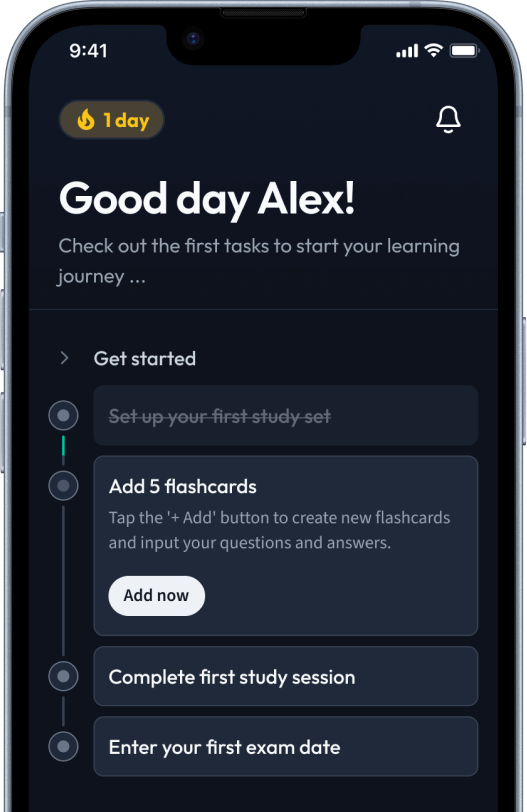

StudySmarter: Study help & AI tools

4.5 • +22k Ratings

More than 22 Million Downloads

Free

As a university economics student, you might be hoping to better understand the answers to big questions like "How does the government know what to do if there's a recession?" Or "What should the central bank do when inflation is out of control?"

Lerne mit deinen Freunden und bleibe auf dem richtigen Kurs mit deinen persönlichen Lernstatistiken

Jetzt kostenlos anmeldenAs a university economics student, you might be hoping to better understand the answers to big questions like "How does the government know what to do if there's a recession?" Or "What should the central bank do when inflation is out of control?"

The deeper you go into the world of economics, the more complex these questions can become. But the good news is that at a high level, the explanations are not nearly as mysterious as most people believe. In fact, by the time you're done reading this, you might very well be able to explain these things very elegantly. The fundamental analysis is done with the help of the aggregate supply and demand model.

Keep reading if you want to sound like the smartest person in the room at the next party you go to.

What is the definition of aggregate demand and aggregate supply? Aggregate demand refers to the overall level of demand in the economy. Aggregate supply refers to the overall level of supply in the economy. Imagine all consumers in a market, whatever their demand, added up together: this forms the aggregate demand. On the other hand, imagine all the firms supplying all sorts of goods you can possibly think of: this forms aggregate supply. 'Aggregate' simply means 'total' in economics.

Aggregate demand refers to the overall level of demand in an economy.

Aggregate supply refers to the overall level of supply in the economy.

A high-level analysis of Aggregate Demand (AD) and Aggregate Supply (AS) requires an understanding of each of the key components and how they interact. The reason why is that the interaction between these important ideas gives policymakers the clues needed to answer questions like "How do we reduce unemployment?" And "What should we do if inflation and unemployment are at unacceptable levels?"

Let's dive into each concept briefly.

When you think of Aggregate Demand (AD), you only need to look as far as yourself and your friends. Quite simply, the concept behind AD is that there is a direct relationship between aggregate price levels and aggregate output demanded in an economy.

More precisely, the relationship is an inverse, or negative one because the higher price levels are, the less "stuff" you will be able to buy, all things being equal.

Economists define the groups that compose AD into four broad categories: Consumer Spending (C), Business Investment Spending (I), Government Spending (G), and Net Exports (X-M).

The formula used to quantify the level of aggregate output demanded is as follows:

When examined graphically, the relationship between price levels and quantities demanded is illustrated in Figure 1.

As you can see in Figure 1, there is a negative relationship between aggregate price levels and the aggregate quantity of output demanded.

When the demand for an individual good or service changes at a given price, this results in a shift in the demand curve for that good or service. Similarly, when the AD for all goods and services changes at given aggregate price levels, this results in a shift in the AD curve.

What factors can cause a shift in the AD curve? Well, several.

Some of the most important factors that can cause AD to change include changes in consumer and business expectations, changes in fiscal or monetary policy, changes in wealth, and changes in the capital in an economy.

For example, if consumers expect to have more disposable income in the near future, their current demand will likely increase at given price levels, shifting the AD curve to the right.

Similarly, if firms expect economic conditions to worsen in the near future resulting in depressed sales, they will likely adjust their current expenditures.

Two of the most important causes of shifts in Aggregate Demand include Fiscal and Monetary Policy.

Fiscal Policy can come in two forms. The first is the spending on final goods and services by governments. In other words, the G in GDP = C + I + G + (X - M). Since government spending directly impacts GDP, governments can increase or decrease their spending to effect rightward or leftward shifts in aggregate demand correspondingly.

In addition to direct spending on final goods and services, governments can also put fiscal policy into action by changing tax rates, thereby increasing or decreasing after-tax income for households and companies.

Both direct spending and tax rate changes by governments can impact aggregate demand so as to produce changes in GDP and price levels in response to economic situations.

Similarly, central banks can use Monetary Policy to generate shifts in aggregate demand, and by extension, impacts to GDP and price levels. Generally speaking, central banks can change the money supply or interest rates in an economy through a set of tools at their disposal. These changes to the money supply and interest rates will then have effects on Consumer and Business Investment spending, in other words, the C and I in GDP = C + I + G + (X - M).

In its simplest form, when the central bank changes the money supply, an imbalance between the supply of money and the demand for money leads to changes in interest rates in order to re-establish equilibrium in the money market. When interest rates change, so too will the savings behavior of households. In addition, since firms generally use loans to make capital investments, changes to interest rates make those loans either more or less expensive, thereby directly impacting the desire for firms to invest.

Check out our StudySmarter explanations for Fiscal Policy and Monetary Policy to better understand these powerful economic policy tools.

The corresponding partner to Aggregate Demand is Aggregate Supply.

Aggregate Supply is effectively the relationship between price levels in an economy and the amount of final goods and services firms are willing to produce.

Aggregate Supply slopes upwards because, all else being equal, the higher aggregate prices are in an economy, the more output of final goods and services, or GDP, firms are willing to produce.

In order to better understand Aggregate Supply, we'll begin by diving into the Short-Run Aggregate Supply curve.

The short-run aggregate supply curve shows a positive relationship between aggregate price levels and the amount of final goods and services firms are willing to produce.

In order to better understand this positive relationship and the upward-sloping nature of the aggregate supply curve, it's important to understand the concept of profitability in general terms.

Broadly speaking, a firm's profit can be described with a very simple and intuitive formula:

Since there is a direct positive relationship between a firm's profit, and the price of the good or service it produces, the aggregate supply curve also has a positive relationship, hence the upward slope of the aggregate supply curve.

You'll notice that the second part of the profitability formula is centered around the cost to produce a unit of output. Costs of production come in many forms, but in general, employee wages usually comprise the largest portion of production costs. Moreover, in the short run, these costs are largely inflexible.

Wages in particular are generally inflexible in the short-run because of previously agreed upon labor contracts, as well as informal agreements, or conditions that exist that prevent firms from changing the wages they pay their employees. Economists use nominal wages, or the actual dollar amounts firms pay to their employees, to explain these costs in the short run.

For example, if a firm lowers the nominal wages it pays its employees, some or many employees may leave that firm to work for its competitor. The existence of minimum wages also has an impact on the slow-moving nature of nominal wages in the short run. This is why wages are said to be "sticky" in the short run.

While not all costs are "sticky" like nominal wages tend to be, it's still true that many production costs can't be changed easily in the short run. As a result, the short-run aggregate supply curve slopes upward because, at higher prices, producers make higher profits, so they will produce more. If short-run costs haven't changed despite a rise in the aggregate price level, even better for producers. Figure 2 shows the positive relationship between the aggregate price level and aggregate supply.

As you can imagine, when a change in the aggregate price levels is met with a corresponding change in the aggregate production level, this is a movement along the short-run aggregate supply curve.

However, if you're wondering if the short-run aggregate supply curve can shift, the answer is a definitive yes.

What would cause such a shift? In order to answer that question, we must first ask ourselves "What would cause firms in an economy to produce more or less output at any given aggregate price level"?

You probably wouldn't have to think too long to realize that sudden changes in the costs of production in the short-run affect unit profit.

For example, if a key cost of production suddenly increases, all else being equal, then all firm's unit profits will decrease at any given aggregate price level. So if the price of oil or electricity suddenly increases, this would cause a leftward shift in the short-run aggregate supply curve.

A less intuitive factor that can cause a shift in the short-run aggregate supply curve is a change in overall productivity.

Productivity, in its simplest form, is the amount or rate of output a unit of input can produce in a given amount of time. So, for example, if a change in technology allows employees to be able to increase their level or rate of production in an hour, all else being equal, that means that more goods and services can be produced without changes to the costs of inputs, which will increase unit profit. And since we know that increases in unit profit lead to increases in aggregate output at any given price, this would result in a rightward shift in the short-run aggregate supply curve.

The long-run aggregate supply curve does away with the idea that factors of production have fixed costs because, in the long-run, input costs can be very flexible indeed. Nominal wages, for example, can be renegotiated in the long run.

In fact, economists believe that prices of goods and services, as well as prices for production inputs, are flexible in the long run if we consider the formula by which firms make decisions. You can see that both unit profit variables are flexible in the long run. For example, if both output prices and input prices double, unit profitability doesn't change; therefore output doesn't change.

The idea of full input and output price flexibility in the long run explains why the long-run aggregate supply curve is vertical. In other words, the level of output doesn't change as aggregate prices change as shown in Figure 3 below.

Moreover, there is something very interesting about the precise location, or level of output, of the long-run aggregate supply curve. As it turns out, the output, or GDP, the long-run aggregate supply curve identifies is what economists call the economy's potential output. In other words, the long-run aggregate supply curve level of output if all prices, including nominal wages, are fully flexible is an economy's level of potential output.

Potential output is the GDP an economy would produce if all prices, including input and output prices, were fully flexible and all resources were being used efficiently.

In order to understand how the economy works at the macro level, you need look no further than the Aggregate Demand (AD) - Aggregate Supply (AS) model.

As with most economic concepts, generally speaking, the equilibrium point between AD and AS tells us a great deal. It's at the point where AD and AS meet that helps us gauge how well the economy is doing in two very important ways: aggregate price levels (inflation) and aggregate output (GDP).

The easiest way to understand this concept is by examining it in a visual format, or graphically.

The first step in determining the health of the economy in graphical form is to place the Aggregate Demand and Aggregate Supply curves onto the same graph, as demonstrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4 illustrates the location at which AD and AS intersect (Point A), which is where the market is in short-run equilibrium and both producers and consumers are satisfied. More specifically, Point A in Figure 4 informs economists of the equilibrium aggregate price level (PA) and the equilibrium output (GDPA) level. Put another way, it's at this point that the amount of output supplied is equal to the amount of output demanded.

We know that, in the long run, the economy is at its potential level of output where the long-run aggregate supply is located. To an economist, long-run macroeconomic equilibrium is achieved if aggregate demand, short-run aggregate supply, and long-run aggregate supply all intersect at the same spot as illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5 illustrates the level of real GDP that economists would identify as the long-run macroeconomic equilibrium point.

However, what would happen if this were not the case? In fact, it's precisely in that scenario that the Government and Central Bank often choose to get involved.

Assume, for example, that the economy was at long-run equilibrium one year ago, but a negative Supply Shock occurred that caused a leftward shift in the short-run AS curve as illustrated in Figure 6 below.

As you can see from Figure 6, once the economy has re-established equilibrium, it has done so below potential output (GDPLRE) creating a recessionary gap and higher unemployment. Moreover, the new short-run equilibrium is at higher aggregate prices, which means higher inflation. This is the worst of both worlds indeed.

In a situation like this, two corrective actions could be taken in the short run. First, the Government could use Fiscal Policy to increase its spending and shift the AD curve to the right to re-establish output at GDPLRE. Alternatively, the Central Bank could use Monetary Policy to increase the money supply resulting in a lower interest rate, inducing households to save less and spend more, and firms to invest in more capital projects, thereby shifting the AD curve to the right to re-establish GDPLRE. Either of these policies would work to re-establish long-run equilibrium.

What would happen, however, if neither the Government nor the Central Bank decided to intervene in the short run?

The beauty of the long run is that all prices have time to become flexible again and adjust to economic conditions. In the face of high unemployment over the long-run, nominal wages will fall because of competitive labor market conditions and adjusting formal and informal contracts. As a result, firms' profitability will increase, inducing a rightward shift in short-run AS, until GDPLRE is re-established as illustrated in Figure 7.

While this may seem ideal, it could take years to occur and the economy and its constituents may have to suffer through high prices and high unemployment for a very long time.

There exists one other method to calculating GDP that bears mentioning. That approach is the Value-Added approach.

The Value-Added approach to calculating GDP is one where the value of all final goods and services produced in an economy are added up, while being very careful to exclude the value of all the intermediate goods and services used to produce the final goods and services.

The reason economists are careful to avoid including the value of intermediate goods and services is to avoid double-counting.

For example, when you buy a smartphone, it's reasonable and correct to assume that the manufacturer of that cell phone has to account for all of the costs it incurred to manufacture the phone when deciding what final price it should charge. That means that the cost of the electronic components the firm bought to produce the smartphone are already built into the price the manufacturer charges you. So if economists were to also count the value of all intermediate goods, such as the electronic components of the smartphone, they would be double-counting and overestimating the true value of GDP in an economy.

Fiscal Policy is spending on final goods and services by governments, as well as the setting of tax rates.

Monetary Policy is the changes in the money supply, and subsequently, interest rates, done by central banks.

Aggregate Demand slopes downward, indicating the negative relationship between aggregate prices and output demanded. Short-run Aggregate Supply slopes upwards, indicating the positive relationship between prices and output supplied.

Aggregate Demand slopes downward, indicating the negative relationship between aggregate prices and output demanded. Short-run Aggregate Supply slopes upwards, indicating the positive relationship between prices and output supplied. When graphed together, their intersection provides the economy's equilibrium aggregate price level and aggregate output, or GDP.

The Aggregate Demand curve describes the negative relationship between aggregate prices and output demanded. The Short-run Aggregate Supply curve describes the positive relationship between prices and output supplied.

Aggregate prices, input factor costs, and productivity affects aggregate short-run supply, while aggregate prices, wage levels, interest rates, and taxation rates affect aggregate demand.

Short-run Aggregate Supply is the amount of output firms are willing to produce at any given aggregate price, all else being equal. Aggregate Demand is the amount of output demanded by the constituents in the economy at any given price level, all else being equal.

Name two types of aggregate supply.

Short-run and Long-run

Which is the vertical aggregate supply curve?

The long-run aggregate supply curve

Who suggested the other concept of LRAS?

Keynesians.

What are the types of the output gap?

What is the equation of aggregate demand?

AD=C+I+G+(X-M)

What is the definition of Investment in the context of aggregate demand?

Investment is essentially planned demand for capital goods needed for the production of other goods and services.

Already have an account? Log in

Open in AppThe first learning app that truly has everything you need to ace your exams in one place

Sign up to highlight and take notes. It’s 100% free.

Save explanations to your personalised space and access them anytime, anywhere!

Sign up with Email Sign up with AppleBy signing up, you agree to the Terms and Conditions and the Privacy Policy of StudySmarter.

Already have an account? Log in