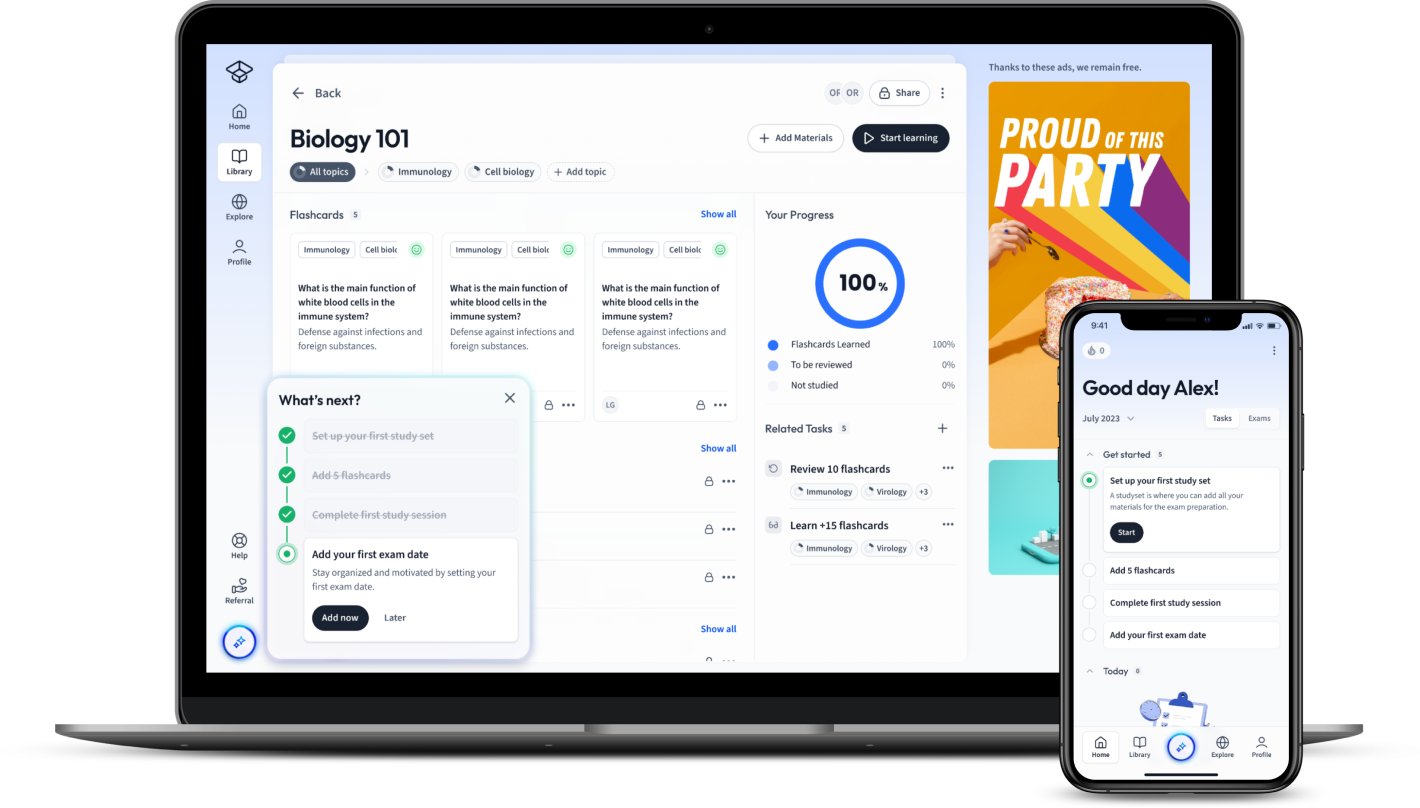

StudySmarter: Study help & AI tools

4.5 • +22k Ratings

More than 22 Million Downloads

Free

Did it ever occur to you that the burgers at McDonald's are not exactly the same as the burgers at Burger King? Do you know why that is? And what does the market of fast-food chains have in common with the market of electricity or the global oil market? Do you want to learn more about imperfect competition and how most markets work in the real world? Read on to find out the difference between perfect and imperfect competition and more!

Lerne mit deinen Freunden und bleibe auf dem richtigen Kurs mit deinen persönlichen Lernstatistiken

Jetzt kostenlos anmeldenDid it ever occur to you that the burgers at McDonald's are not exactly the same as the burgers at Burger King? Do you know why that is? And what does the market of fast-food chains have in common with the market of electricity or the global oil market? Do you want to learn more about imperfect competition and how most markets work in the real world? Read on to find out the difference between perfect and imperfect competition and more!

The best way to understand imperfect competition is to look at the differences between perfect and imperfect competition.

In a perfectly competitive market, we have many firms that are selling the same undifferentiated products - think about produce: you can find the same vegetables sold at different grocery stores. In such a perfectly competitive market, firms or individual producers are price takers. They can only charge a price that is the market price; if they charge a higher price, they will lose their customers to all the other firms selling the same products at the market price. In the long-run equilibrium, firms in perfectly competitive markets don't make economic profits after we account for the opportunity costs of not being able to use the resources for other purposes.

You might be wondering: how is it possible that firms operate with no economic profits in the long run? That is not really how things work in the real world, right? Well, you are certainly not wrong - many firms in the real world do manage to make a handsome profit, even after accounting for opportunity costs. That's because most of the markets that we have in the real world are not perfectly competitive markets. In fact, we rarely have perfect competition in reality, save for the produce markets.

For a refresher, read our explanation: Perfect Competition.

Here is the definition of imperfect competition.

Imperfect competition refers to market structures that are less competitive than perfect competition. These include monopolistic competition, oligopoly, and monopoly.

Figure 1 below shows the different kinds of market structures on a spectrum. They range from the most competitive to the least competitive from left to right. In perfect competition, there are many firms selling the same product; in monopolistic competition, there are many firms competing with differentiated products; an oligopoly has only a couple or a few firms; and in a monopoly, there's only one firm serving the entire market.

You bet we have an explanation on all these topics!

Check out:

Imperfect competition has some peculiar characteristics which make it different from perfect competition. Let's consider some of them!

A hallmark of an imperfectly competitive market is that the marginal revenue (MR) curve facing the firms lies below the demand curve, as Figure 2 shows below. There is a smaller number of competing firms under imperfect competition - in the case of monopolistic competition, there are many firms, but they are not perfect competitors due to product differentiation. Firms in these markets have some influence over the demand for their products, and they can charge a price that is higher than the marginal cost of production. In order to sell more units of the product, the firm must lower the price on all units - this is why the MR curve is below the demand curve.

On the other hand, there are many firms selling homogeneous products in a perfectly competitive market. These firms have no influence over the demand they face and have to take the market price as given. Any individual firm that operates in such a perfectly competitive market faces a flat demand curve because if it charges a higher price, it will lose all its demand to competitors. For an individual firm under perfect competition, its marginal revenue (MR) curve is the demand curve, as shown in Figure 3. The demand curve is also the firm's average revenue (AR) curve because it can only charge the same market price no matter the quantity.

One important implication of imperfect competition has to do with firms' ability to make economic profits. Recall that in the case of a perfectly competitive market, firms have to take the market price as given. Firms in perfect competition do not have a choice because as soon as they charge a higher price, they will lose all their customers to their competitors. The market price in perfectly competitive markets is equal to the marginal cost of production. As a result, firms in perfectly competitive markets are only able to break even in the long run, after all costs (including opportunity costs) are taken into account.

On the other hand, firms in imperfectly competitive markets have at least some power in setting their prices. The nature of imperfectly competitive markets means that consumers can't find perfect substitutes for these firms' products. This allows these firms to charge a price that is higher than the marginal cost and to turn a profit.

Imperfect competition leads to market failures. Why is that? This actually has to do with the marginal revenue (MR) curve being below the demand curve. In order to maximize profit or minimize loss, all firms produce to the point where marginal cost equals marginal revenue. From a societal perspective, the optimal output is the point where marginal cost equals demand. Since the MR curve is always below the demand curve in imperfectly competitive markets, the output is always lower than the socially optimal level.

In Figure 4 below, we have an example of an imperfectly competitive market. The imperfect competitor faces a marginal revenue curve that is below the demand curve. It produces up to the point where marginal revenue equals marginal cost, at point A. This corresponds to point B on the demand curve, so the imperfect competitor charges consumers at a price of Pi. In this market, the consumer surplus is area 2, and area 1 is the profit that goes to the firm.

Contrast this situation to a perfectly competitive market. The market price is equal to the marginal cost at Pc. All the firms in this perfectly competitive market will take this price as given and jointly produce a quantity of Qc at point C, where the market demand curve for the entire industry intersects with the marginal cost curve. The consumer surplus under perfect competition would be the combination of areas 1, 2, and 3. So, the imperfectly competitive market leads to a deadweight loss of the size of area 3 - this is the inefficiency caused by imperfect competition.

There are three types of imperfectly competitive market structures:

Let's go through these, one by one.

You may have noticed that the term "monopolistic competition" has both the words "monopoly" and "competition" in it. This is because this market structure has some characteristics of a perfectly competitive market and also some characteristics of a monopoly. Like in a perfectly competitive market, there are many firms because the barriers to entry are low. But unlike in perfect competition, the firms in monopolistic competition are not selling identical products. Instead, they sell somewhat differentiated products, which gives the firms some degree of monopoly power over the consumers.

Fast-food chains

Fast-food chain restaurants are a classic example of monopolistic competition. Think about it, you have many fast-food restaurants to choose from on the market: McDonald's, KFC, Burger King, Wendy's, Dairy Queen, and the list goes on even longer depending on what region you are in the US. Can you imagine a world with a fast-food monopoly where there's just McDonald's that sells burgers?

Fig. 5 - A cheeseburger

Fig. 5 - A cheeseburger

All these fast-food restaurants sell essentially the same thing: sandwiches and other usual American fast-food items. But also not exactly the same. The burgers at McDonald's are not the same as the ones sold at Wendy's, and Dairy Queen has ice creams that you can't find from the other brands. Why? Because these businesses deliberately make their products a little bit different - that's product differentiation. It's certainly not a monopoly because you have way more than one choice, but when you are craving that specific kind of burger or ice cream, you have to go to that one specific brand. Because of this, the restaurant brand has the power to charge you a little more than in a perfectly competitive market.

We certainly invite you to learn more on this topic here: Monopolistic Competition.

In an oligopoly, there are only a few firms selling to the market because of high barriers to entry. When there are only two firms in the market, it's a special case of oligopoly called duopoly. In an oligopoly, firms do compete with one another, but the competition is different from the cases of perfect competition and monopolistic competition. Because there are only a small number of firms in the market, what one firm does affects the other firms. In other words, there is an interdependent relationship between the firms in an oligopoly.

Imagine that there are only two firms selling the same potato chips at the same price on the market. It's a duopoly of chips. Naturally, each firm would want to capture more of the market so that they can earn more profits. One firm can try to take customers from the other firm by lowering the price of its potato chips. Once the first firm does this, the second firm would have to lower its price further to try to take back the customers that it has lost. Then the first firm would have to lower its price again... all this back and forth until the price reaches the marginal cost. They can't lower the price further at this point without losing money.

You see, if oligopolists are to compete without cooperation, they might reach a point where they operate just like firms in perfect competition - selling with a price equal to the marginal cost and making zero profits. They don't want to make zero profits, so there is a strong incentive for oligopolists to cooperate with each other. But in the U.S. and many other countries, it is illegal for firms to cooperate with each other and fix prices. This is done to ensure that there's healthy competition and to protect consumers.

OPEC

It's illegal for firms to cooperate and fix prices, but when the oligopolists are countries, they can do just that. The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) is a group made up of oil-producing countries. The explicit aim of OPEC is for its member countries to agree on how much oil they produce so that they can keep the oil price at a level that they like.

To learn more, click here: Oligopoly.

On the very far end of the market competitiveness spectrum lies a monopoly.

A monopoly is a market structure where one firm serves the entire market. It is the polar opposite of perfect competition.

A monopoly exists because it's very difficult for other firms to enter such a market. In other words, high barriers to entry exist in this market. There are a number of reasons for a monopoly to exist in a market. It can be the case that a firm controls the resource that is required to make the product; governments in many countries often grant permission for only one state-owned firm to operate in a market; intellectual property protections give firms a monopoly right as a reward for their innovation. Besides these reasons, sometimes, it is "natural" that there's only one firm operating in the market.

A natural monopoly is when the economies of scale make sense for just one firm to serve the entire market. Industries where natural monopolies exist usually have a large fixed cost.

Utilities as natural monopolies

Utility companies are common examples of natural monopolies. Take the electric grid for example. It would be very expensive for another company to come in and build all the electric grid infrastructure. This large fixed cost essentially prohibits other firms from entering the market and becoming a grid operator.

Fig. 6 - Power grid infrastructure

Fig. 6 - Power grid infrastructure

What are you waiting for? To learn more, click on our explanation: Monopoly.

The interaction between oligopolistic firms is like playing a game. When you are playing a game with other players, how well you do in that game depends not only on what you do but also on what the other players do. One of the uses of game theory for Economists is to help understand the interactions between firms in oligopolies.

Game theory is the study of how players act in situations where one player's course of action influences the other players and vice versa.

Economists often use a payoff matrix to show how players' actions lead to different outcomes. Let's use the example of the potato chips duopoly. There are two firms selling the same potato chips at the same price on the market. The firms face a decision of whether to keep their prices at the same level or to lower the price in order to try and take customers from the other firm. Table 1 below is the payoff matrix for these two firms.

Game theory payoff matrix | Firm 1 | ||

Keep price as before | Drop price | ||

Firm 2 | Keep price as before | Firm 1 makes the same profit Firm 2 makes the same profit | Firm 1 makes more profit Firm 2 loses its market share |

Drop price | Firm 1 loses its market share Firm 2 makes more profit | Firm 1 makes less profitFirm 2 makes less profit | |

Table 1. Game theory payoff matrix of the potato chips duopoly example - StudySmarter

If both firms decide to keep their prices as they are, the outcome is the top left quadrant: both firms make the same profits as before. If either firm drops the price, the other will follow suit to try to recapture the market share that they lose. This will continue until they reach a point where they can't drop the price any lower. The outcome is the bottom right quadrant: both firms still split the market but make less profit than before - in this case, zero profit.

In the potato chips duopoly example, there is a tendency for both firms to lower their prices in an attempt to capture the entire market in the absence of an enforceable agreement between the two duopolists. The likely outcome is the one shown in the bottom right quadrant of the payoff matrix. Both players are worse off than if they have just kept their prices as they were. This kind of situation where players tend to make a choice that leads to a worse outcome for all the players involved is called the prisoners' dilemma.

To learn more about this, read our explanations: Game Theory and Prisoners' Dilemma.

The markets that we usually talk about are product markets: the markets for goods and services that consumers buy. But let's not forget there's also imperfect competition in the factor markets as well. Factor markets are markets for the factors of production: land, labor, and capital.

There is one form of imperfectly competitive factor market: Monopsony.

Monopsony is a market where there's only one buyer.

A classic example of a monopsony is a large employer in a small town. Since people can't seek work elsewhere, the employer has market power over the local labor market. Similar to an imperfectly competitive product market where firms have to lower prices in order to sell more units, the employer in this case has to raise the wage to hire more workers. Since the employer has to raise the wage for every worker, it faces a marginal factor cost (MFC) curve that is above the labor supply curve, as shown in Figure 7. This results in the firm hiring a fewer number of workers Qm at a lower wage Wm than in a competitive labor market, where the number of workers hired would be Qc, and the wage would be Wc.

To learn more, read our explanation: Monopsonistic Markets.

Imperfect competition describes any market structures that are less competitive than perfect competition. These include monopolistic competition, oligopoly, and monopoly.

In a monopoly, there is only one firm serving the entire market. There is no competition.

The marginal revenue curve lies below the demand curve. The firms can charge a price higher than the marginal cost. The output is lower than the social optimum. There are market inefficiencies created by imperfect competition.

In perfect competition, there are many firms selling a homogeneous good. In reality, this rarely happens, and we have different types of imperfectly competitive markets.

Product markets: monopolistic competition, oligopoly, and monopoly. Factor markets: monopsony.

What is a firm’s main objective?

Profit maximisation.

Who are the customers of a firm?

Individual customers, businesses, or governments.

What are the financial goals of a firm?

Profit maximisation, market share expansion.

What is a firm's profit?

The difference between the total costs and revenues.

How to maximise a firm’s profit?

Profit is maximised when marginal costs equal marginal revenues.

What are some non-financial objectives of a firm?

Customer satisfaction, job satisfaction, corporate social responsibility.

Already have an account? Log in

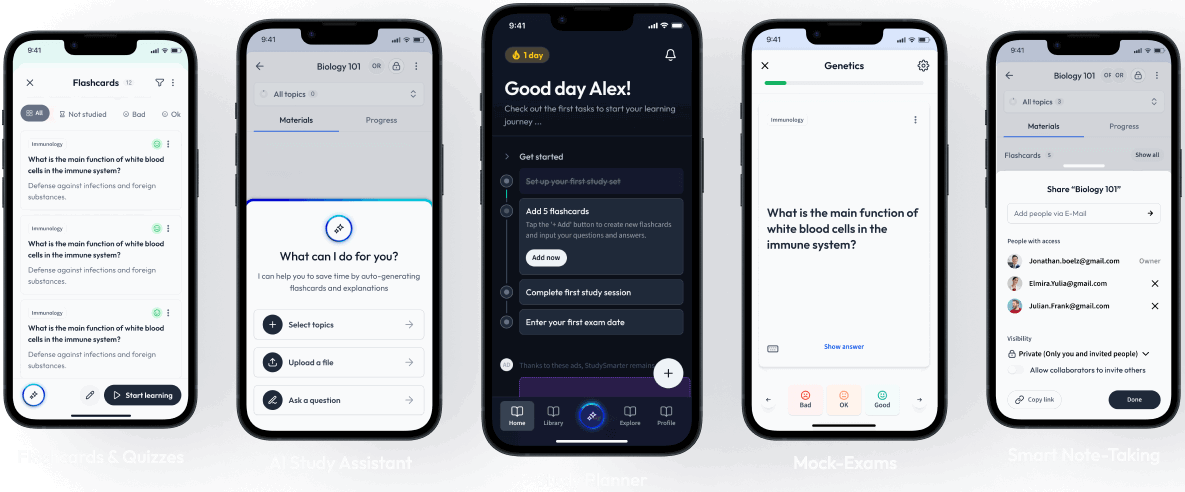

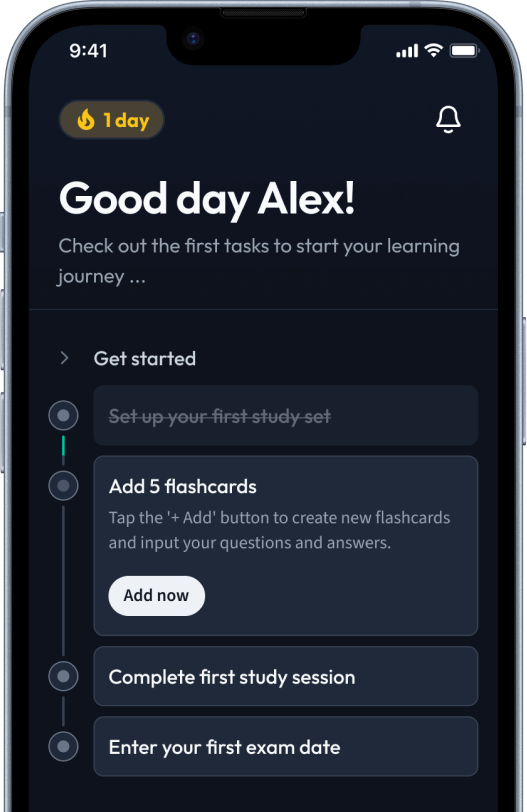

Open in AppThe first learning app that truly has everything you need to ace your exams in one place

Sign up to highlight and take notes. It’s 100% free.

Save explanations to your personalised space and access them anytime, anywhere!

Sign up with Email Sign up with AppleBy signing up, you agree to the Terms and Conditions and the Privacy Policy of StudySmarter.

Already have an account? Log in