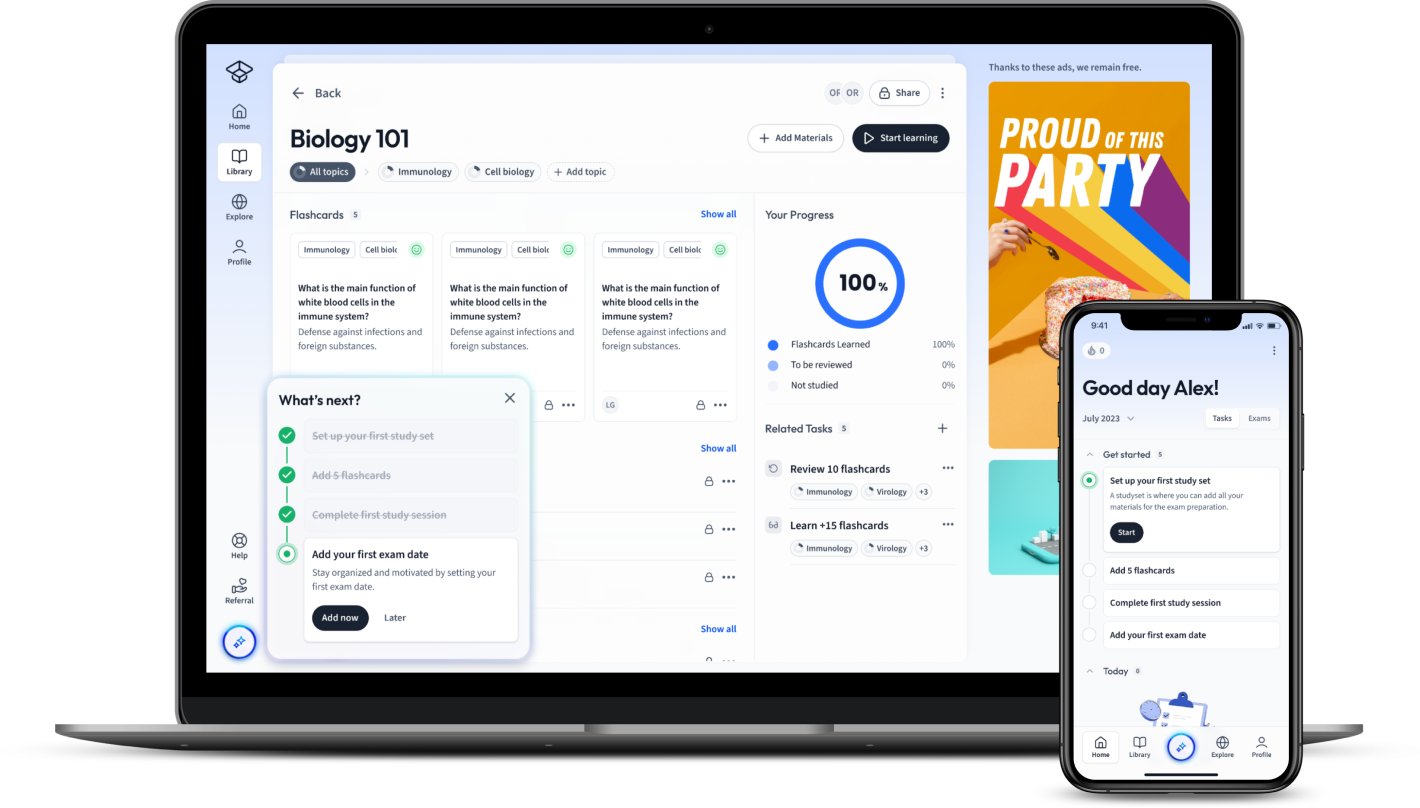

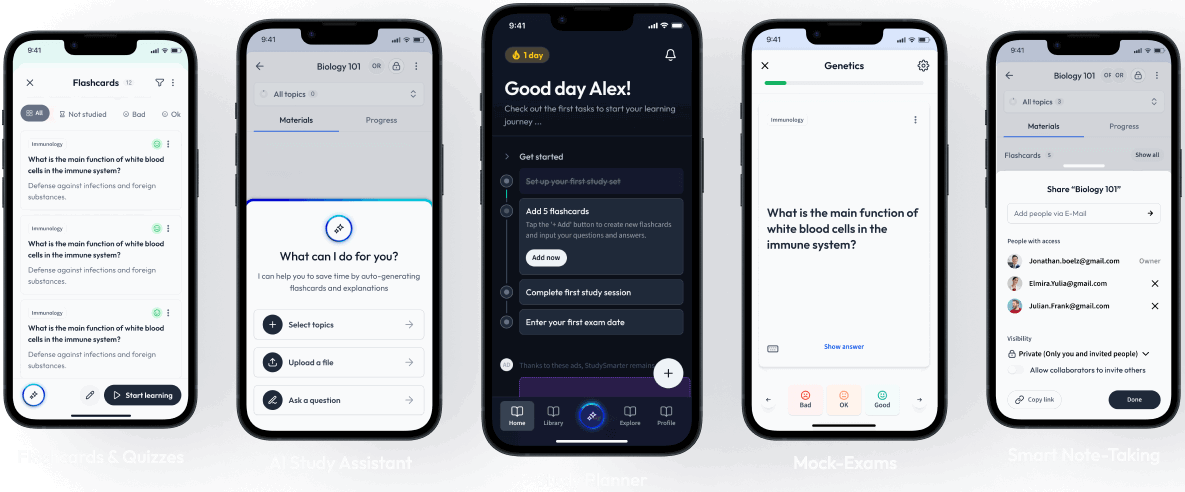

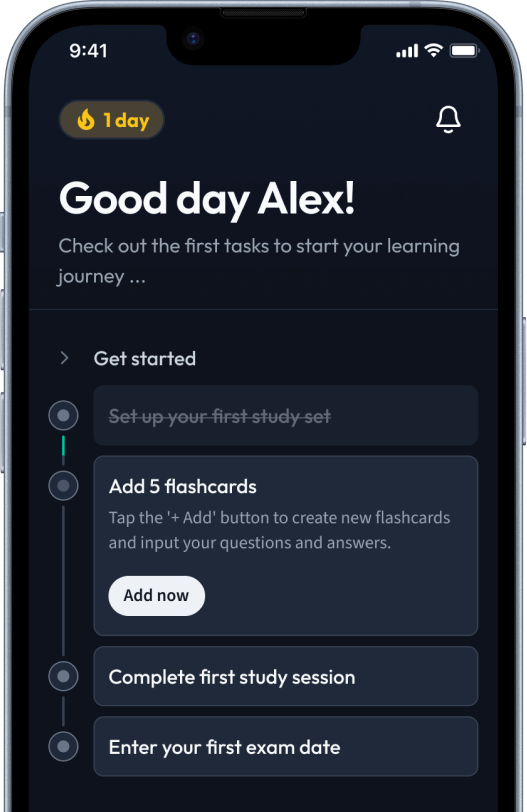

StudySmarter: Study help & AI tools

4.5 • +22k Ratings

More than 22 Million Downloads

Free

Organisms continually take in and interpret chemical signals from our environment. Living cells are also constantly exchanging signals with each other. Such signals are crucial for maintaining cell health and function and for initiating biological processes including cell division and cell death.

Lerne mit deinen Freunden und bleibe auf dem richtigen Kurs mit deinen persönlichen Lernstatistiken

Jetzt kostenlos anmeldenOrganisms continually take in and interpret chemical signals from our environment. Living cells are also constantly exchanging signals with each other. Such signals are crucial for maintaining cell health and function and for initiating biological processes including cell division and cell death.

In this article, we will discuss how these signals are transmitted within the cell through signal transduction pathways. We will also go through various examples of signal transduction pathways and some of the diagrams.

The term signal transduction pathway is used to describe the branched molecular network through which signaling molecules are sequentially activated (or deactivated) to carry out a specific cellular function. The signal transduction pathway is set off when a ligand binds to a cell-surface receptor during cell signaling.

Cell signaling is the process by which a cell responds to messages from its external environment through protein receptors. When a ligand binds to a receptor--a protein that is found inside or on the surface of the target cell--a signal is transmitted, triggering a specific cellular process.

A signal transduction pathway has three basic stages:

Signal reception: The cell detects a signal when a chemical signal called a ligand binds to a receptor protein on the cell surface.

Signal transduction: The signaling molecule changes the cell-surface receptor protein. The signal is relayed by each molecule changing the next molecule in the pathway.

Cellular response: The signal initiates a specific cellular process.

The process of signal transduction is depicted in Figure 1 below.

Molecules that deliver signals are called ligands, while the protein molecules in the cell to which ligands bind are called receptors. When a ligand binds to an internal receptor, the signal does not need to be passed onto other receptors or messengers. On the other hand, when a ligand binds to a cell-surface receptor, the signal is passed on to other molecules in a process called signal transduction.

In a signal transduction pathway, second messengers, enzymes, and activated proteins interact with specific proteins, which are consequently activated in a chain reaction that converts extracellular signals to intracellular signals and ultimately triggers a specific cellular response.

Interactions that take place before a certain point are called upstream events, while those that take place after such point are called downstream events.

Most of the cell's proteins can influence downstream processes depending on the conditions within the cell. The interaction of two or more signaling pathways can cause a single pathway to branch off toward different endpoints. In addition, the same ligands are frequently involved in the transmission of different signals in different cell types. The difference in response is linked to variations in protein expression among cell types. Another factor is the signal integration of the pathways, which occurs when signals from two or more separate cell-surface receptors combine to trigger the same cell response.

Enzymatic cascades can also enhance the impact of extracellular signals. The signal may be initiated when a single ligand binds to a single receptor. However, the activation of an enzyme-linked receptor can activate several copies of a signaling cascade component, amplifying the signal.

Because of these complications, a signal transduction pathway can be better described as a branching network than a linear chain.

Once the signal is relayed from the external environment of the cell into the inner surface of the plasma membrane, it can take two major routes toward the cell interior depending on the type of receptor that is activated, that is, by second messenger or by protein recruitment.

The first type of receptor transmits a signal from its cytoplasmic region to an adjacent enzyme–called an effector–which produces a second messenger. Second messengers are small intracellular mediators that either activate or deactivate certain proteins. It can either diffuse through the cytosol or stay embedded in the plasma membrane. Second messengers tend to be more prominent in the signaling pathway when a rapid, widespread response is needed.

An example of a second messenger is the calcium ion (Ca2+) which, in response to a signal, is released in large quantities and quickly diffused through the cytosol. Calcium ions are responsible for the mediation and coordination of skeletal muscle cell contraction. Like calcium ions, other water-soluble second messengers including cAMP and cGMP diffuse through the cytosol. On the other hand, lipid-soluble messengers such as diacylglycerol (DAG) diffuse through the interior of the plasma membrane where other key signaling proteins are embedded.

Second messengers are named as such because extracellular signaling molecules (such as hormones) are considered the “first messengers”. However the term second messenger may be misleading because there could be over ten messengers in a signaling pathway, and the so-called second messenger can actually be the seventh messenger.

The second type of receptor transmits a signal by changing the shape of its cytoplasmic region to become a recruiting station for signaling proteins. Such proteins interact with each other or with components of the plasma membrane.

Whereas second messengers are small and are able to diffuse quickly and broadly, proteins are much larger and less mobile. This means proteins cannot rapidly relay and amplify signals. However, they are able to perform more complex signaling roles. This is because proteins have the capacity to carry out specific interactions with other proteins. They also show binding specificity for ligands and other molecules. Furthermore, their activity can be regulated.

When the signal is transmitted (whether by second messenger or protein recruitment) a protein at the start of an intracellular signaling pathway is activated. Each signaling pathway consists of a number of unique proteins that function sequentially. The majority of signaling proteins are proteins with several domains, which enable them to engage with a variety of players simultaneously or sequentially. As such, while it is often described as a linear chain, in reality, the signal transduction pathway is more often a branching network that allows for the integration, diversification, and modification of responses.

Proteins in a signaling pathway tend to function by changing the shape of the next protein in the series, which either activates or inhibits that protein. These shape changes are usually done by protein kinases that add phosphate groups. Protein kinases are like the "on switch" of the signal transduction pathway--when a protein kinase phosphorylates (or adds a phosphate group to) another protein, it triggers a chain reaction and causes proteins to be phosphorylated one after the other.

On the other hand, there are also protein phosphatases that dephosphorylate or remove phosphate groups from other proteins which deactivates protein kinases. They basically function as the "off switch" of the signal transduction pathway. To make sure that the cellular response is properly regulated when the signal is no longer present, it is crucial to turn off the signal transduction pathway. Dephosphorylation also frees up protein kinases for future use, allowing the cell to react again to subsequent signals.

Signals transmitted eventually reach target proteins that are responsible for specific cellular processes. The response caused by the target protein can lead to modifications such as:

A change in gene expression

A change in metabolic enzyme activity

A reorientation of the cytoskeleton

A change in ion permeability

An increase or decrease in cell mobility

The activation of DNA synthesis

The activation of apoptosis or programmed cell death

Signaling can be terminated by eliminating the extracellular messenger molecule. This is carried out by specific enzymes that destroy corresponding molecules. There are also cases in which active receptors are internalized by the cell and degraded together with its ligand.

Signal transduction pathways often interact with one another; when they do, they perform logical operations to trigger a response. For example, a response could require a logical "AND" (meaning all pathways involved must be active in order to trigger the response). A different response could require a logical "OR" in which the activation of either pathway would lead to the response.

Now that we have discussed the basics of the signal transduction pathway, let’s move on to specific examples of signaling transduction pathways.

Here we will discuss the JAK-STAT pathway that plays a role in the transcription of the casein gene during milk production. We will also discuss the Hedgehog Pathway which plays an important role in limb and neural differentiation in vertebrates.

Receptor kinases are a type of membrane-bound receptor protein capable of phosphorylation (adding phospate groups to other proteins). Receptor tyrosine kinases (RTK) are receptor kinases that add phosphate groups to tyrosine residue. RTK are activated when a ligand binds to it, causing the RTK to undergo dimerization (two molecules forming a chemical bond), which then activates its phosphorylation function.

The JAK-STAT pathway transmits information from the cell membrane to the nucleus. It plays an important role in the activation of the gene called casein during milk production.

STAT–which stands for signal transducers and activators of transcription–proteins make up the transcription factors that are phosphorylated by some receptor tyrosine kinases (RTK) such as the JAK family.

An endocrine factor called prolactin binds to the extracellular domains of prolactin receptors, resulting in their dimerization. Each of these receptors have a JAK protein kinase bound to them, and with these JAK proteins now brought together, they can phosphorylate the receptors in various sites.

The JAK proteins transform receptors into an RTK. With this, the receptors are now ready to phosphorylate inactive STATs, resulting in their dimerization. The dimers formed are actually the active form of the STAT transcription factors, so they are ready to be moved to the nucleus where they will bind to certain parts of DNA.

In the case of milk production, these transcription factors will bind to the upstream promoter elements of casein, which initiates its transcription.

Members of the Hedgehog protein family bind to protein receptors known as Patched. Patched proteins bind to a signal transducer, the Smoothened protein, and prevents it from functioning.

If Hedgehog does not bind to Patched, the Smoothened protein is not active, and a protein called Cubitus interruptus (Ci) is tethered to the responding cell’s microtubules. The Ci is cleaved while on the microtubules in a way that allows a segment to enter the nucleus and function as a transcriptional repressor. This segment of the Ci protein inhibits transcription by attaching to the enhancers and promoters of specific genes.

On the other hand, if Hedgehog binds to Patched, the Patched protein's shape changes so that it no longer inhibits Smootshened. The entire Ci protein can now move to the nucleus and function as a transcriptional activator of the same genes it would have otherwise repressed.

In vertebrates, the Hedgehog pathway is crucial for limb and neural differentiation. Mice that were bred to be homozygous for a mutant allele of Sonic Hedgehog showed severe limb deformities in addition to cyclopia, or having a single eye in the middle of the forehead (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2: Image depicting two different types of cyclopia.

Fig. 2: Image depicting two different types of cyclopia.

Signal transduction pathways enable signals to be relayed from the external environment to the inside of the cell, triggering specific responses such as cell division and cell death.

The term signal transduction pathway is used to describe the branched molecular network through which signaling molecules are sequentially activated (or deactivated) to carry out a specific cellular function.

Protein phosphatases dephosphorylate or remove phosphate groups from other proteins, which deactivates protein kinases. They basically function as the "off switch" of the signal transduction pathway.

The three steps to a signal transduction pathway are reception, transduction, and response.

Signal transduction pathways often interact with one another; when they do, they perform logical operations to trigger a response. For example, a response could require a logical "AND" (meaning all pathways involved must be active in order to trigger the response). A different response could require a logical "OR" in which the activation of either pathway would lead to the response.

This process can be described as a self-destruct mechanism that allows cells to die in a controlled way, preventing potentially harmful molecules from escaping the cell.

Apoptosis

During this process, cells that die swell, burst, and empty their contents onto their neighbors.

Necrosis

During this process, a type of white blood cell envelopes and destroys a foreign substance or removes dead cells. This process plays a role in preventing the contents of dying cells from being released.

Phagocytosis

What enzyme initiates apoptosis by cleaving specific proteins in the nucleus and cytoplasm?

Caspase

Explain the process of caspase cascade.

Caspases are enzymes that cleave specific proteins in the nucleus and cytoplasm. Caspases can be found in all cells as inactive precursors that are activated via cleavage by other caspases. Active caspases cleave and activate other procaspases, resulting in what is called a caspase cascade.

Explain how the mitochondrial process works.

For cell damage to trigger apoptosis, a gene called p53 is required to start the transcription of genes that stimulate the release of cytochrome c--an electron carrier protein--from mitochondria. Once cytochrome c is forced out of mitochondria and into the cytosol, it interacts and activates the adaptor protein Apaf-1. Most forms of apoptosis utilize this mitochondrial pathway of procaspase activation to start, speed up, or intensify the caspase cascade.

Already have an account? Log in

Open in AppThe first learning app that truly has everything you need to ace your exams in one place

Sign up to highlight and take notes. It’s 100% free.

Save explanations to your personalised space and access them anytime, anywhere!

Sign up with Email Sign up with AppleBy signing up, you agree to the Terms and Conditions and the Privacy Policy of StudySmarter.

Already have an account? Log in