StudySmarter: Study help & AI tools

4.5 • +22k Ratings

More than 22 Million Downloads

Free

If you have read our explanation on Cell Structure, you probably know that prokaryotes do not have a nucleus or any other membrane-bound organelles. Prokaryotes are almost exclusively unicellular organisms: they are made up of a single cell. Prokaryotes can, however, form something called colonies. These colonies are interlinked but don’t fulfil all criteria of a multicellular organism.

Lerne mit deinen Freunden und bleibe auf dem richtigen Kurs mit deinen persönlichen Lernstatistiken

Jetzt kostenlos anmeldenIf you have read our explanation on Cell Structure, you probably know that prokaryotes do not have a nucleus or any other membrane-bound organelles. Prokaryotes are almost exclusively unicellular organisms: they are made up of a single cell. Prokaryotes can, however, form something called colonies. These colonies are interlinked but don’t fulfil all criteria of a multicellular organism.

Eukaryotes, on the other hand, are cells with a nucleus. Most often eukaryotes are multicellular. The main types of eukaryotes are animals, plants, fungi, and protists. Protists are special eukaryotic cells that are unicellular organisms. Go to our explanation on the subject if you want to learn more about Eukaryotes.

Viruses are not considered living beings at all because they do not meet the criteria of a living organism. The criteria of a living organism are:

There are two main types of prokaryotes: bacteria and archaea. The main differences are the cell membranes and the conditions in which these prokaryotes are found.

Bacteria have a phospholipid bilayer, whereas archaea have a monolayer. Archaea are only found in extreme conditions such as hot geysers. Bacteria, on the other hand, can be found absolutely everywhere on earth, even in the human body (good bacteria).

Here we will briefly cover the classification and reproduction of bacteria.

Bacteria can be classified through Gram staining or by their shape. Let’s see how these classifications work.

Bacteria can be sub-divided into two main groups: gram-negative and gram-positive. Bacteria are classified in this way by using a gram stain. The Gram stain (which is purple) colours the bacteria’s cell wall, and this determines the overall outcome of the stain.

When we apply the purple Gram stain, it will colour the Gram-positive bacterium in a distinct purple, and the Gram-negative one in a pale red colour. Why do Gram-positive bacteria retain the purple colour? This is because Gram-positive bacteria have a thick peptidoglycan cell wall.

Where does the red colour come from in the Gram-negative bacteria? From the counterstain, safranin.

Safranin is used as a counterstain in the Gram test to help distinguish between the two types of bacteria. Scientists can use other counterstains depending on the nature of the experiment/the stain.

Examples of Gram-positive bacteria include Streptococcus. Examples of Gram-negative ones include chlamydia and Helicobacter pilorii.

By shape

Bacteria can also be classified by their shape. Round bacteria are known as cocci, cylindrical as bacilli, spiral-shaped ones as spirilla, and comma-shaped bacteria as vibrio. There are also other less common types of bacteria such as star or rectangular-shaped ones.

Bacteria mostly reproduce asexually. The most common form of reproduction in bacteria is called binary fission.

Binary fission is a process in which a bacterial cell copies its genetic material, grows, and then splits into two cells, making an exact replica of the mother cell.

Bacterial conjugation involves two bacteria, but it isn't a form of reproduction. During bacterial conjugation, genetic information in the form of plasmids is transferred from one cell to another via pili. This often gives the receiving bacteria an advantage, such as antibiotic resistance. This process doesn’t produce a new bacteria. It’s more like a ‘buff’ version of the previous one.

While you won’t need to know too much about archaea, let’s highlight a few things. Next to bacteria, archaea are the other pillar of prokaryotes. They can be found in extreme environments like geysers and volcanoes. They evolved to function best in those environments. Archaea are mostly unicellular.

Some research suggests that archaea could be the origin of eukaryotes, as they share traits with both prokaryotes and eukaryotes.

Viruses are non-living microbes, they are not cells and therefore they are neither prokaryotes nor eukaryotes. This means that they need some kind of host to reproduce as they can’t do it on their own. They do, however, have genetic material, either DNA or RNA. They introduce the DNA or RNA into the host cell. The cell is then manipulated into producing the virus parts, after which it usually dies.

Viruses have fewer components than cells. The basic components are:

Viruses do not have any organelles, which is the reason they cannot make their own proteins; they do not have any ribosomes. Viruses are much smaller than cells and you can almost never see them in a light microscope.

Eukaryotic and prokaryotic cell structures differ. They have some organelles in common, such as the plasma membrane, ribosomes and the cytoplasm. However, membrane-bound organelles are only present in eukaryotes.

Fig. 1. Schematic prokaryotic cell structure.

Fig. 1. Schematic prokaryotic cell structure.

The eukaryotic cell structure is much more complex than the prokaryotic one. Prokaryotes are also usually single-celled, so they can’t ‘create’ specialised structures, whilst eukaryotic cells usually function together and create specialised structures. For example, in the human body, eukaryotic cells form tissues, organs, and organ systems (e.g. the cardiovascular system).

Fig. 2. Animal cells are an example of eukaryotic cells.

Fig. 2. Animal cells are an example of eukaryotic cells.

| Table 1. Differences between prokaryotes, eukaryotes and viruses. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Prokaryotes | Eukaryotes | Viruses |

| Cell type | Simple | Complex | Not a cell |

| Size | Small | Large | Very small |

| Nucleus | No | Yes | No |

| Genetic material | DNA, circular | DNA, linear | DNA, RNA, single or double, linear or circular |

| Reproduction | Asexual (binary fission) | Sexual or asexual | Replication (uses host cell machinery) |

| Metabolism | Varied | Varied | None (obligate intracellular) |

Here's a Venn diagram aid to help you understand what prokaryotes, eukaryotes and viruses have in common and where they differ.

Fig. 3. Venn diagram comparing eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells and viruses.

Fig. 3. Venn diagram comparing eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells and viruses.

Viruses can infect plants, animals, humans, and prokaryotes.

A virus often causes an illness in the host by inducing cell death. Most often, viruses only ever infect one species, like humans. A virus that infects prokaryotes will never infect a human, for example. However, there are instances where a virus can infect different animals.

A common example of the effect of viruses in prokaryotic cells are the bacteriophages. These are a group of viruses that only infect bacteria.

Viruses infect host cells by:

For more information on the replication please visit our explanation on Viral Replication.

Below you will find a diagram showing the infection through bacteriophages.

Fig. 4. Lytic cycle of a bacteriophage.

Fig. 4. Lytic cycle of a bacteriophage.

Bacteria are usually grown in cultures using a medium with nutrients in which they can quickly multiply. The multiplication of bacteria is exponential, because the number of bacteria always doubles: from one to four, to eight, etc. This means that bacteria replicate very quickly and can often be viewed under a light microscope.

Viruses, however, are much smaller and can’t simply grow on their own. They need a cell to grow in and can most commonly only be seen under an electron microscope. For comparison, the average size of bacteria is approximately 2 micrometers whereas the average size of a virus is between 20 and 400 nanometers.

Viruses can infect both prokaryotes and eukaryotes, causing disease or cell death.

Viruses are not considered alive as they are not capable of replicating without a host cell.

They can both cause diseases in eukaryotes.

These are called bacteriophages.

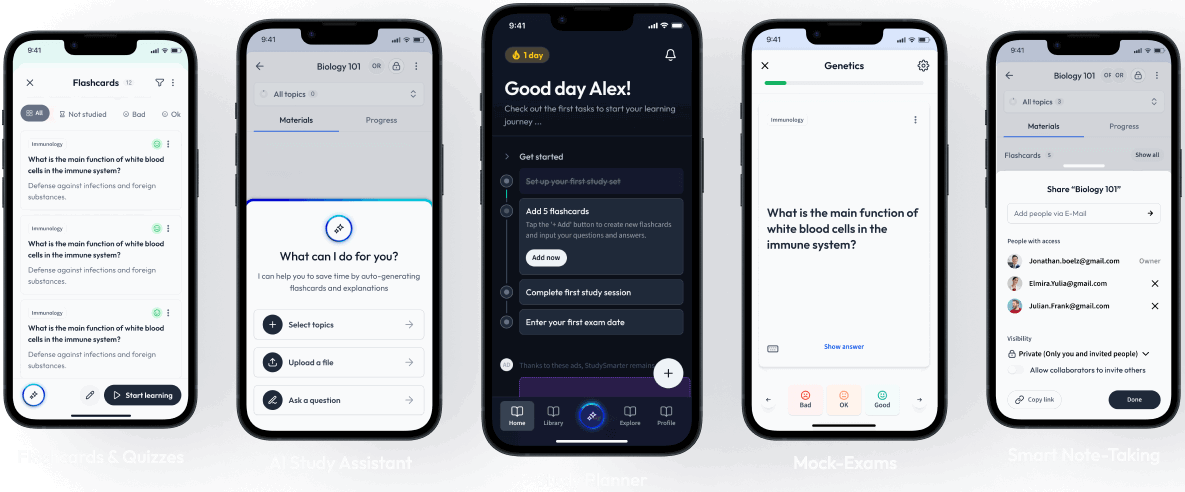

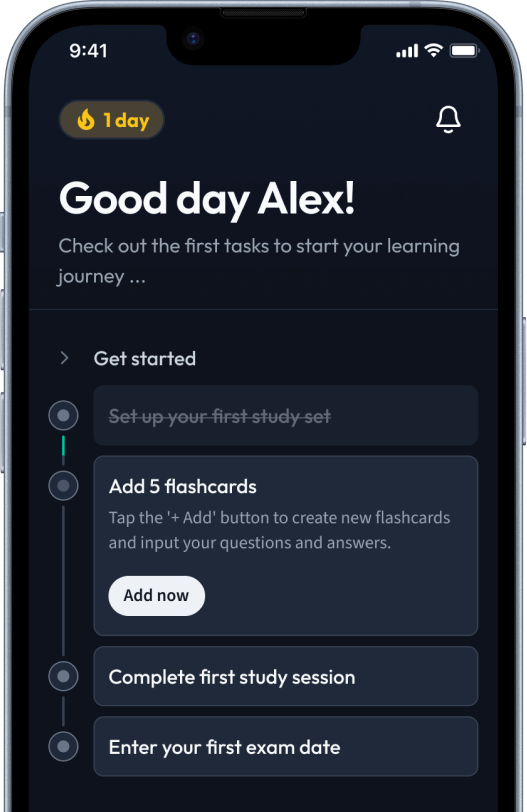

The first learning app that truly has everything you need to ace your exams in one place

Sign up to highlight and take notes. It’s 100% free.

Save explanations to your personalised space and access them anytime, anywhere!

Sign up with Email Sign up with AppleBy signing up, you agree to the Terms and Conditions and the Privacy Policy of StudySmarter.

Already have an account? Log in