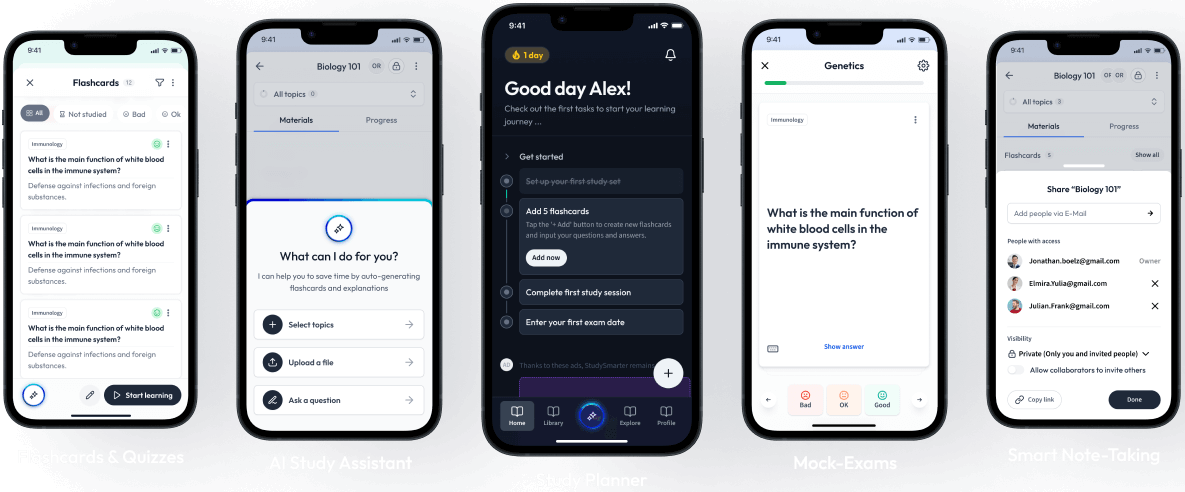

StudySmarter: Study help & AI tools

4.5 • +22k Ratings

More than 22 Million Downloads

Free

Lerne mit deinen Freunden und bleibe auf dem richtigen Kurs mit deinen persönlichen Lernstatistiken

Jetzt kostenlos anmeldenIf you've ever spent time around toddlers, the following scene should be familiar. The toddler is excited! They are taking some of their very first steps, and maybe they're moving a little too fast. OUCH! They stumble and fall, scraping their knee on the ground.

To the toddler, this might be one of their very first injuries, and it's a big deal! Perhaps the skin on their knees is gone forever! It's hard to explain to a child that their leg will heal when they're feeling pain, but let's zoom in on this moment.

The skin cells from their knees really are gone for now, but not forever. How is it that this skin returns? The skin cells left over have a lot of work to do. These cells will have to produce clones, copies of themselves in a process called the cell cycle and cell division.

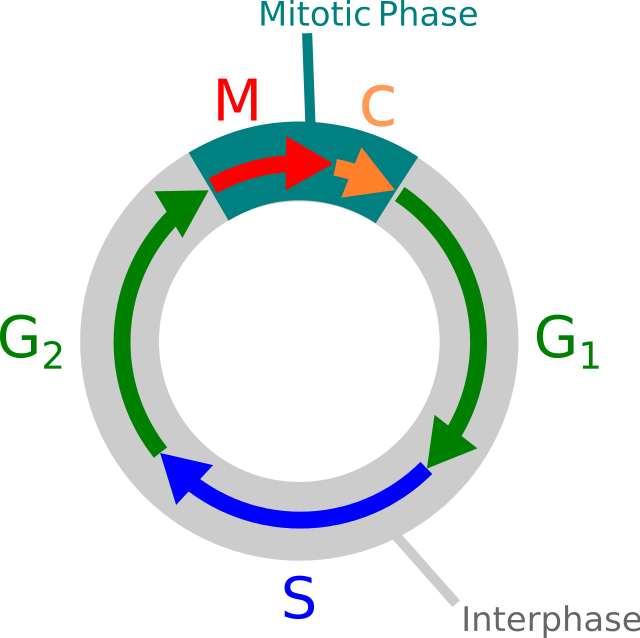

The cell cycle describes the life cycle of a eukaryotic cell as it performs its necessary functions and prepares for cell division, producing two new daughter cells. The cell cycle is split into two phases: the interphase and the mitotic phase. Figure 1 shows the diagram of the cell cycle.

Figure 1: The cell cycle: Interphase and the Mitotic phase, as well as the sub-phases: G1, S, G2, Mitosis, and Cytokinesis. Source: Wikipedia.org

The cell cycle phases, interphase and the mitotic phase, are further broken down into sub-phases: G1, S phase, and so on. Let's explore each of these phases and sub-phase of the cell cycle more thoroughly:

Interphase is the longest portion of the cell cycle, where the cell performs its essential functions and prepares for division. Interphase is broken down into three sub-phases: first gap phase (G1), synthesis phase (S phase), and second gap phase (G2). These cell cycle phases are described briefly below:

The cell performs all of its necessary functions.

Accumulates energy and proteins in preparation for the synthesis phase.

The cell grows so that it is large enough to be divided in two.

The first cell checkpoint ensures the cell is ready to move on to S phase.

The cell undergoes DNA Replication, copying exactly all of the DNA chromosomes.

The chromosomes now form the recognizable X-shape, each half of the X being a full copy of the other side. Each half is called a sister chromatid.

Organelles called centrosomes are duplicated.

The cell continues to grow and accumulate energy for the mitotic phase.

The organelles are duplicated for each daughter cell.

The cytoskeleton is dismantled into microtubules to be used during mitosis.

A second cell checkpoint ensures the cell is ready to enter the mitotic phase.

The mitotic phase of the cell cycle is when the cell separates its DNA chromosomes and cell components, leading to cell division and daughter cells. The mitotic phase consists of two sub-phases that occur simultaneously: mitosis and cytokinesis. Mitosis is the division of the DNA chromosomes and takes place over five sub-phases: prophase, prometaphase, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase. The deep dive below gives a brief overview of the sub-phases of mitosis. Cytokinesis is when cell division actually happens, producing daughter cells. In animal cells, an actin ring pinches the cell's plasma membrane together until it has split into two cells, almost like pinching a piece of clay into two. Plant cells, however, build a cell plate inside itself until it fuses with its outer cell wall and separates the two new daughter cells. With cytokinesis complete, the cell cycle is also complete and may begin once again for each of the daughter cells.

Immediately after the mitosis cell division, the new cell may enter a quiescent stage called gap zero (G0) of the cell cycle, and will not continue to actively divide. This may be a temporary stage while the organism is under stress, before the cell moves into the G1 after some outside stimulus. Or it can be permanent in the case of nerve or heart cells that do not actively divide once fully formed.

Imagine, for a moment, that the cell did not have all the energy or proteins necessary to complete DNA replication. Maybe some of the chromosomes were completely copied, others only partly copied, and some not at all. How would this affect mitosis or the daughter cells that divide from this parent cell?

It could be disastrous! The daughter cells might immediately die, or live but be unable to complete their function, or continue dividing without stop causing cancer. To prevent this the cell tightly regulates the cell cycle using "checkpoints" between G1 and S phase, G2 and mitotic phase, and during metaphase of mitosis.

Moving into the S phase of the cell cycle is the point of no return for cell division, often called the restriction point. Once the chromosomes start to replicate the cell is committed to becoming two new cells. This first checkpoint in the cell cycle monitors if the cell is ready to complete DNA replication using extracellular signals, such as growth factors. The cell also checks its chromosomes for DNA damage. If damage is detected, it will pause the cell cycle. The cell may then try to repair the DNA if it can or move into G0 until it is ready or triggered to move into the S phase by another signal.

This checkpoint looks to ensure that the cell is large enough and has enough energy to complete the cell cycle with mitosis and cytokinesis. But the main regulation that occurs here inspects the cell's DNA. If the chromosomes are not duplicated, or if they are damaged in some way, the cell stops the cell cycle and tries to fully replicate or repair the chromosomes, before continuing onto mitosis.

This checkpoint happens during mitosis after the chromosomes are aligned on the metaphase plate, right before anaphase separates the chromosomes into what will become the daughter cells. This checkpoint ensures that the spindle microtubules have attached to the duplicated chromosomes correctly at the kinetochores. If microtubules are not attached correctly, the daughter cells may end up with too much or too little DNA, and the cell will halt mitosis until the spindle fibers are attached correctly. If everything gets fixed, the cell cycle will continue, finishing mitosis and cytokinesis.

While the checkpoints take stock of the cell at certain, predetermined points, there are also intracellular molecules that help to push the cell along the cell cycle, or stop the cell cycle if they "notice" something is wrong. Molecules that help to continue the cell cycle engage in positive regulation, while molecules that may stop the cell cycle engage in negative regulation.

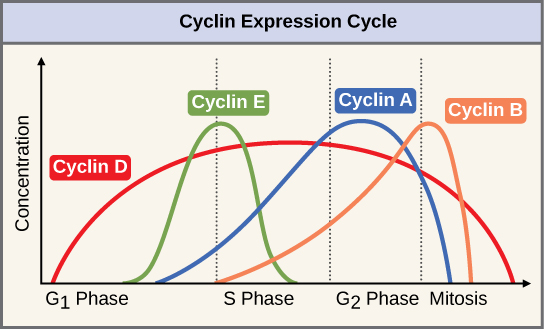

The key proteins that help to advance the cell cycle are called cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases (Cdks). There are four cyclins that change in concentration to help to regulate the cell cycle (Fig. 2). As their concentrations increase in the cell, triggered by internal and external signals, the cyclins help to move the cell cycle into the next phase. After the cyclin initiates the next phase, they are quickly degraded.

Figure 2: The concentration of cyclin molecules during the cell cycle. Source:

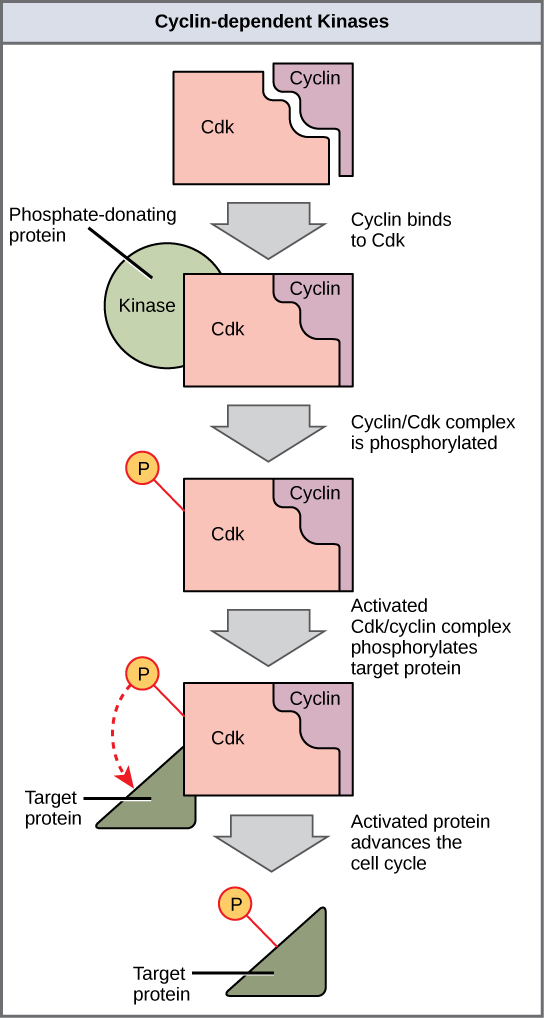

Cyclins cannot act on their own and must bind to a Cdk. After the cyclin has bonded with a Cdk, it must also be phosphorylated by another kinase, to activate the cyclin/Cdk complex. Each phosphorylated cyclin/Cdk complex has a specific shape to bind and phosphorylate the next protein in the cell cycle regulation (Fig. 3). While the amount of cyclin fluctuates a lot during the cell cycle, the amount of cyclin-dependent kinases stay relatively constant but inactive until their specific cyclin protein is present to continue the cell cycle.

Figure 3: Cyclin and cyclin-dependent kinases bind and are activated via phosphorylation from another kinase. The activated cyclin/cdk complex can now activate its target protein and advance the cell cycle. Source: openstax.org

The main negative regulatory molecules for the cell cycle include retinoblastoma protein (Rb), p53, and p21. These proteins are called tumor-suppressors because they were discovered while investigating cancer cells, when the cell cycle continues indefinitely, ignoring the cell cycle checkpoints. Rb, p53, and p21 work primarily at the restriction point: the G1/S phase checkpoint.

P53 is a main regulator in moving into S phase because it looks for and manages damaged DNA during G1 preparation. If p53 finds any damaged DNA, it will increase in concentration, stop the cell cycle, then recruit proteins to repair the DNA. Sometimes DNA cannot be repaired, and so p53 will trigger apoptosis, programmed cell death, instead of allowing the cell to continue the cell cycle.

P21 is produced when there is enough p53 in the cell. P21 acts directly on cyclin and cdks by binding to the cyclin/cdk complex, inhibiting their ability to phosphorylate and progress the cell cycle. As p53 detects problems in the cell, the concentration of p53 and p21 increases, preventing the cell cycle from continuing.

Rb primarily monitors the cell size. When the cell is too small, rb will be active and will bind to transcription factors, specifically called E2F, that help to produce proteins needed for the G1/S checkpoint. As the cell grows it can spend energy phosphorylating rb, changing its shape and forcing it to release E2F. Now that E2F is free, it can begin the transcription of the proteins necessary to progress the cell cycle.

Histones are:

Proteins that DNA wraps around to make nucleosomes

Homologous chromosomes are defined as:

Chromosomes that hold the same genes at the same locus.

Prokaryotic chromosomes are stored in the:

Nucleoid

Humans have how many Chromosomes?

46 total chromosomes, 23 pairs of homologous chromosomes.

What is the relationship between chromatin and chromosomes?

Chromatin folds around scaffolding proteins to make Chromosomes.

What is the relationship between nucleosomes and chromatin?

When nucleosomes are wrapped around themselves many times, they are compacted into chromatin.

Already have an account? Log in

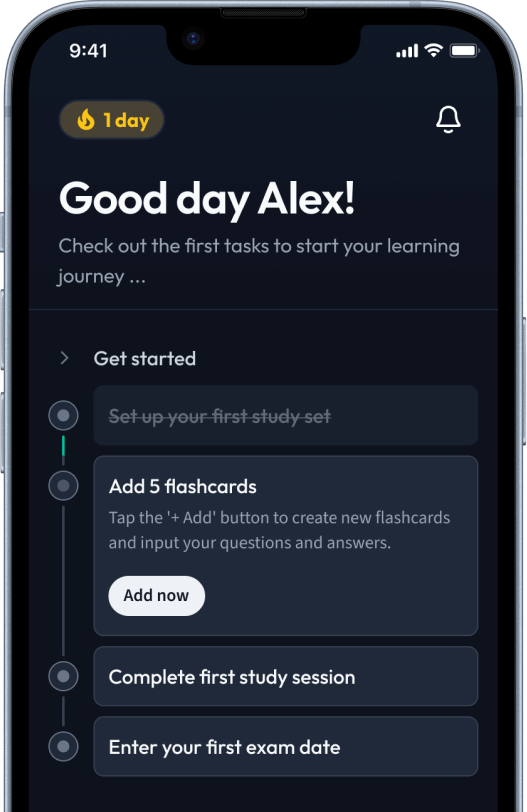

Open in AppThe first learning app that truly has everything you need to ace your exams in one place

Sign up to highlight and take notes. It’s 100% free.

Save explanations to your personalised space and access them anytime, anywhere!

Sign up with Email Sign up with AppleBy signing up, you agree to the Terms and Conditions and the Privacy Policy of StudySmarter.

Already have an account? Log in